Arader Galleries

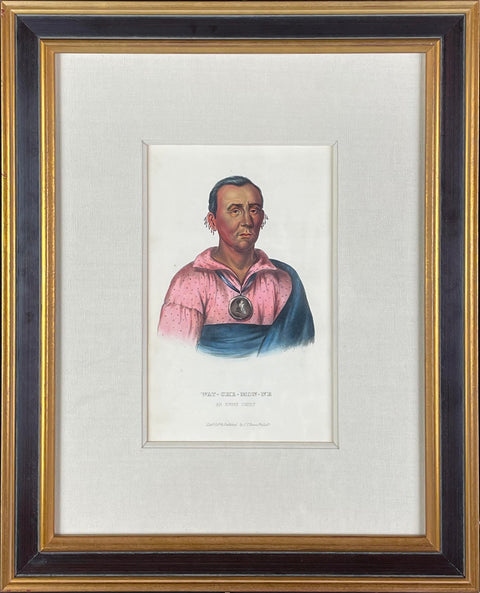

TENS-KWAU-TA-WAW, The Prophet

Pickup currently unavailable

Thomas McKenney (1785-1859) & James Hall (1793-1868)

TENS-KWAU-TA-WAW, The Prophet

From History of the Indian Tribes of North America with Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of the Principal Chiefs

Published: Philadelphia, VOL I: 1837, VOL ll: 1842, VOL lll: 1844

Hand-colored lithograph

Sheet size: approx. 14.5 x 20”

Soon after Thomas L. McKenney was appointed Superintendent of Indian Trade in 1816, he struck upon the idea of creating an archive to preserve the artifacts, implements, and history of the Native Americans. The Archives of the American Indian became the first national collection in Washington and were curated with great care by McKenney through his tenure as Superintendent and also when he served as the first head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs beginning in 1824. Artist Charles Bird King arrived in town in 1822 and, during a visit to his studio, McKenney was inspired to add portraits to the archives. King would, for the following twenty years, capture many of the visiting Indian dignitaries, as well as make copies of watercolors created in the field by the less able James Otto Lewis. Many saw the great value in preserving what was already known to be a vanishing race, but others in government criticized the expenses incurred. The visiting Indian delegations who had come to Washington to meet with the "Great Father" (their name for the president) would inevitably tour the Indian gallery, which was housed in the War Department building, and were generally impressed, many requesting that their portrait be painted and added to the collection. This seemed to help smooth relations during the often tense treaty negotiations.

McKenney was preparing to publish a collection of the Indian portraits when he lost his position at the Bureau during Andrew Jackson's house cleaning in 1830. This seemed like an omen, as many other setbacks befell the project: publishers went bankrupt, investors dropped out, historical information became unobtainable, and expenses soared. McKenney finally enlisted Ohio jurist and writer James Hall to assist with the project, making him a partner. Hall was able to complete the individual biographies of each subject and put the finishing touches on the general history. Six years passed between the original prospectus and the issue of the first part. In that time, James Otto Lewis, who was likely bitter that he would receive no credit for the King-reworked portraits that he sent to the Archives, beat McKenney to the market with his own Aboriginal Port-Folio in 1835. Unfortunately for Lewis, the illustrations were of inferior quality and very few of its later numbers were ever completed. McKenney and Hall's History of the Indian Tribes of North America, on the other hand, was a resounding artistic success. The lithographs were of such high quality, comparable to the best work from Europe, that John James Audubon commissioned the lithographer James T. Bowen to provide illustrations for a revised edition of his Birds of America. Indian Tribes wasn't a financial success, however, for its high price prohibited all but the wealthy and public libraries from subscribing to it. This and the depression after the panic of 1837 both contributed to the work going through several publishers and lithographers before its completion. King's original paintings were eventually transferred to the Smithsonian Institute, where most of them perished in the January 1865 fire. A number of the paintings exist in the form of contemporary copies made by King and his students, but the present work is by far the most complete record of this important collection.

Text accompanying the prophet:

This individual is a person of slender abilities, who acquired great celebrity from the circumstances in which he happened to be placed, and from his connection with the distinguished Tecumthé, his brother. Of the latter, unfortunately, no portrait was ever taken; and, as the two brothers acted in concert in the most important events of ‘their lives, we shall embrace what we have to say of both, in the present article.

We have received, through the politeness of a friend, a narrative of the history of these celebrated Indians, dictated by the Prophet himself, and accurately written down at the moment. It is valuable as a curious piece of autobiography, coming from an unlettered savage, of a race remarkable for tenacity of memory, and for the fidelity with which they preserve and transmit their traditions, among themselves; while it is to be received with great allowance, in consequence of the habit of exaggeration which marks the communications of that people to strangers. In their intercourse with each other, truth is esteemed and practiced; but, with the exception of a few high minded men, little reliance is to be placed upon any statement made by an Indian to a white man. The same code which inculcates an inviolable faith among themselves, justifies any deception towards an enemy, or one of an alien race, for which a sufficient motive may be held out. We know, too, that barbarous nations, in all ages, have evinced a decided propensity for the marvelous, which has been especially indulged in tracing the pedigree of a family, or the origin of a nation. With this prefatory caution, we proceed to give the story of Tenskwautawaw, as related by himself compiled, however, in our own language, from the loose memorandum of the original transcriber.

His paternal grandfather was a Creek, who, at a period which is not defined in the manuscript before us, went to one of the southern cities, either Savannah or Charleston, to hold a council with the English governor, whose daughter was present at some of the interviews. This young lady had conceived a violent admiration for the Indian character; and, having determined to bestow herself upon some “warlike lord” of the forest, she took this occasion to communicate her partiality to her father. The next morning, in the council, the governor inquired of the Indians which of them was the most expert hunter; and the grandfather of Tecumthé, then a young and handsome man, who sat modestly in a retired part of the room, was pointed out to him. When the council broke up for the day, the governor asked his daughter if she was really so partial to the Indians as to prefer selecting a husband from among them; and finding that she persisted in this singular predilection, he directed her attention to the young Creek warrior, for whom, at first sight, she avowed a decided attachment. On the following morning the governor announced to the Creeks, that his daughter was disposed to marry one of their number; and, having pointed out the individual, added, that his consent would be given. The chiefs, at first, very naturally, doubted whether the governor was in earnest; but, upon his assuring them that he was sincere, they advised the young man to embrace the lady and her offer. He was not so un-gallant as to refuse; and, having consented to the fortune that was thus buckled on him, was immediately taken to another apartment, where he was disrobed of his Indian costume by a train of black servants, washed, and clad in a new suit, and the marriage ceremony was immediately performed.

At the close of the council the Creeks returned home, but the young hunter remained with his wife. He amused himself in hunting, in which he was very successful, and was accustomed to take a couple of black servants with him, who seldom failed to bring in large quantities of game. He lived among the whites, until his wife had borne him two daughters and a son. Upon the birth of the latter, the governor went to see his grandson, and was so well pleased that he called his friends together, and caused thirty guns to be fired. When the boy was seven or eight years old the father died, and the governor took charge of the child, who was often visited by the Creeks. At the age of ten or twelve he was permitted to accompany the Indians to their nation, where he spent some time; and, two years after, he again made a long visit to the Creeks, who then, with a few Shawanoes, lived on a river called Pauseekoalaakee, and began to adopt their dress and customs. They gave him an Indian name, Pukeshinwau, which means, something that drops down; and, after learning their language, he became so much attached to the Indian mode of life, that, when the governor sent for him, he refused to return. He married a Creek woman, but afterwards discarded her, and united himself with Methoataaskee, a Shawanoe, who was the mother of Tecumthé, and our narrator, the Prophet. The oldest son by this marriage was Cheeseekau; and, six years afterwards, a daughter was born, who was called Menewaulaakoosee; then a son, called Sauawaseekau, soon after whose birth, the Shawanoes determined to remove to other hunting-grounds. His wife, being unwilling to separate from her tribe, Pukeshinwau accompanied them, after first paying a visit to his grandfather. At parting, the governor gave him a written paper, and told him, that upon showing it at any time to the Americans, they would grant any request which he might make: but that he need not show it to French traders, as it would only vex them, and make them exclaim, sacre Dieu. His family, with about half the Shawanoes, then removed to old Chilicothe; the other half divided again, a part remaining with the Creeks, and the remainder going beyond the Mississippi. Tecumthé was born on the journey. Pukeshinwau was killed at the battle of Point Pleasant, in the autumn of 1774, and the Prophet was born the following winter.

The fourth child of this family was Tecumthé the fifth, Nehaaseemoo, a boy and the sixth, the Prophet, whose name was, originally, Laulewaasikaw, but was changed, when he assumed his character of Prophet, to Tenskwautawaw, or the Open door. Tecumthé was ten years older than the Prophet; the latter was one of three brothers, born at a birth, one of whom died immediately after birth, while the other, whose name was Kumskaukau, lived until a few years ago. The eldest brother had a daughter, who, as well as a daughter of Tecumthé, is living beyond the Mississippi. No other descendant of the family remains, except a son of Tecumthé, who now lives with the Prophet.

Fabulous as the account of the origin of this family undoubtedly is, the Prophet’s information as to the names and ages of his brothers and sisters may be relied upon as accurate, and as affording a complete refutation of the common report, which represents Tenskwautawaw and Tecumthé as the offspring of the same birth.

The early life of the Prophet was not distinguished by any important event, nor would his name ever have been known to fame, but for his connection with his distinguished brother. Tecumthé was a person of commanding talents, who gave early indications of a genius of a superior order. 1 While a boy he was a leader among his playmates, and was in the habit of arranging them in parties for the purpose of fighting sham battles. At this early age his vigilance, as well as his courage, is said to have been remarkably developed in his whole deportment. One only exception is reported to have occurred, in which this leader, like the no less illustrious Red Jacket, stained his youthful character by an act of pusillanimity. At the age of fifteen he went, for the first time, into battle, under the charge of his elder brother, and at the commencement of the engagement ran off, completely panic-stricken. This event, which may be considered as remarkable, in the life of an individual so conspicuous through his whole after career for daring intrepidity, occurred on the banks of Mad River, near the present site of Dayton. But Tecumthé possessed too much pride, and too strong a mind, to remain long under the disgrace incurred by a momentary weakness, and he shortly after wards distinguished himself in an attack on some boats descending the Ohio. A prisoner, taken on this occasion, was burnt, with all the horrid ceremonies attendant upon this dreadful exhibition of savage ferocity; and Tecumthé, shocked at a scene so unbecoming the character of the warrior, expressed his abhorrence in terms so strong and eloquent, that the whole party came to the resolution that they would discontinue the practice of torturing the prisoners at the stake. A more striking proof of the genius of Tecumthé could not be given; it must have required no small degree of independence and strength of mind, to enable an Indian to arrive at a conclusion so entirely at variance with all the established usages of his people; nor could he have impressed others with his own novel opinions without the exertion of great powers of argument. He remained firm in the benevolent resolution thus early formed; but we are unable to say how far his example conduced to the extirpation of the horrid rite to which we have alluded, and which is now seldom, if at all, practiced. Colonel Crawford, who was burned in 1782, is the last victim to the savage propensity for revenge, who is known to have suffered this cruel torture.

Tecumthé seems to have been connected with his own tribe by slender ties, or to have had a mind so constituted as to raise him above the partiality and prejudices of clanship, which are usually so deeply rooted in the Indian breast. Throughout his life he was always acting in concert with tribes other than his own. In 1789, he removed, with a party of Kickapoo, to the Cherokee country; and, shortly after, joined the Creeks, who were then engaged in hostilities with the whites. In these wars, Tecumthé became distinguished, often leading war parties some times attacked in his camp, but always acquitting himself with ability. On one occasion, when surrounded in a swamp, by superior numbers, he relieved himself by a masterly charge on the whites; through whose ranks he cut his way with desperate courage. He returned to Ohio immediately after Harmer’s defeat, in 1791; he headed a party sent out to watch the movements of St. Clair, while organizing his army, and is supposed to have participated in the active and bloody scenes which eventuated in the destruction of that ill-starred expedition.

In 1792, Tecumthe, with ten men, was attacked by twenty-eight whites, under the command of. the celebrated Simon Kenton, and, after a spirited engagement, the latter were defeated; and, in 1793, he was again successful in repelling an attack by a party of whites, whose numbers were superior to his own.

The celebrated victory of General Wayne, in which a large body of Indians, well organized, and skillfully led, was most signally defeated, took place in 1794, and produced an entire change in the relations then existing between the American people and the aborigines, by crushing the power of the latter at a single blow, and dispersing the elements of a powerful coalition of the tribes. In that battle, Tecumthe led a party, and was with the advance which met the attack of the infantry, and bore the brunt of the severest fighting. When the Indians, completely, over powered, were compelled to retreat, Tecumthe, with two or three others, rushed on a small party of their enemies, who had a field-piece incharge, drove them from the gun, and cutting loose the horses, mounted them, and fled to the main body of the Indians.

In 1795 Tecumthe again raised a war party, and, for the first time, styled himself a chief, although he was never regularly raised to that dignity; and, in the following year, he resided in Ohio, near Piqua. Two years afterwards, he joined the Delawares, in Indiana, on White river, and continued to reside with them for seven years.

About the year 1806, this highly-gifted warrior began to exhibit the initial movements of his great plan for expelling the whites from the valley of the Mississippi. The Indians had, for a long series of years, witnessed with anxiety the encroachments of a population superior to themselves in address, in war, and in all the arts of civil life, until, having been driven beyond the Alleghany ridge, they fancied that nature had interposed an impassable barrier between them and their oppressors. They were not, however, suffered to repose long in this imaginary security. A race of hardy men, led on step by step in the pursuit of game, and in search of fertile lands, pursued the footsteps of the savage through the fastnesses of the mountains, and explored those broad and prolific plains, which had been spoken of before, in reports supposed to be partly fabulous, but which were now found to surpass in extent, and in the magnificence of their scenery and vegetation, all that travelers had written, or the most credulous had imagined. Individuals and colonies began to emigrate, and the Indians saw that again they were to be dispossessed of their choicest hunting-grounds. Wars followed, the history of which we have not room to relate wars of the most unsparing character, fought with scenes of hardy and romantic valor, and with the most heart-rending incidents of domestic distress. The vicissitudes of these hostilities were such as alternately to flatter and alarm each party; but as year after year rolled away, the truth became rapidly developed, that the red men were dwindling and re i ding, while the descendants of the Europeans were increasing in numbers, and pressing forward with gigantic footsteps. Coalitions of the tribes began to be formed, but they were feebly organized, and briefly united. A common cause roused all the tribes to hostility, and the whole frontier presented scenes of violence. Harmer, St. Clair, and other gallant leaders, sent to defend the settlements, were driven back by the irritated savages, who refused to treat on any other condition than that which should establish a boundary to any farther advance of the whites. Their first hope was to exclude the latter from the valley of the Mississippi; but, driven from this position by the rapid settlement of western Pennsylvania and Virginia, they assumed the Ohio river as their boundary, and proposed to make peace with General Wayne, on his agreeing to that stream as a permanent line between the red and white men. After their defeat by that veteran leader, all negotiation for a permanent boundary ceased, the tribes dispersed, each to fight its own wars, and to strike for plunder or revenge, as opportunity might offer.

Tecumthe seems to have been, at this time, the only Indian who had the genius to conceive, and the perseverance to attempt, an extended scheme of warfare against the encroachment of the whites. His plan embraced a general union of all the Indians against all white men, and proposed the entire expulsion of the latter from the valley of the Mississippi. He passed from tribe to tribe, urging the necessity of a combination which should make a common cause; and burying, for a time, all feuds among them selves, wage a general war against the invader who was expelling them, all alike, from their hunting-grounds, and who would not cease to drive them towards the setting sun, until the last remnant of their race should be hurled into the great ocean of the West.

This great warrior had the sagacity to perceive, that the traffic with the whites, by creating new and artificial wants among the Indians, exerted a powerful influence in rendering the latter dependent on the former; and he pointed out to them, in forcible language, the impossibility of carrying on a successful war while they depended on their enemies for the supply of articles which habit was rendering necessary to their existence. He showed the pernicious influence of ardent spirits, the great instrument of savage degradation and destruction; but he also explained, that in- using the guns, ammunition, knives, blankets, cloth, and other articles manufactured by the whites, they had raised up enemies in their own wants and appetites, more efficient than the troops of their oppressors. He urged them to return to the simple habits of their fathers to reject all superfluous ornaments, to dress in skins, and to use such weapons as they could fabricate, or wrest by force from the enemy; and, setting the example, he lived an abstemious life, and sternly rejected the use of articles purchased from the traders.

Tecumthé was not only bold and eloquent, but sagacious and subtle; and he determined to appeal to the prejudices, as well as the reason, of his race. The Indians are very superstitious; vague as their notions are respecting the Deity, they believe in the existence of a Great Spirit, to whom they look up with great fear and reverence; and artful men have, from time to time, appeared among them, who have swayed their credulous minds, by means of pretended revelations from Heaven. Seizing upon this trait of the Indian character, the crafty projector of this great revolution prepared his brother, Tenskwautawaw, or Ellsquatawa, (for the name is pronounced both ways,) to assume the character of a Prophet; and, about the year 1806, the latter began to have dreams, and to deliver predictions. His name, which, previous to this time, was Olliwachica, was changed to that by which he was afterwards generally known, and which signifies “the open door” by which it was intended to represent him as the way, or door, which had been opened for the deliverance of the red people.

Instead of confining these intrigues to their own tribe, a village was established on the Wabash, which soon became known as the Prophet’s town, and was for many years the chief scene of the plots formed against the peace of the frontier. Here the Prophet denounced the white man, and invoked the malediction of the Great Spirit upon the recreant Indian who should live in friendly intercourse with the hated race. Individuals from different tribes in that region Miamis, Wea, Piankashaw, Kickapoo, Delaware, and Shawanoes collected around him, and were prepared to execute his commands. The Indians thus assembled, were by no means the most reputable or efficient of their respective tribes, but were the young, the loose, the idle; and here, as is the case in civilized societies, those who had least to lose were foremost in jeopardy the blood and property of the whole people. The chiefs held back, and either opposed the Prophet or stood uncommitted. They had, doubtless, intelligence enough to know that he was an impostor; nor were they disposed to encourage the brothers in assuming to be leaders, and in the acquisition of authority which threatened to rival their own. Indeed, all that portion of the surrounding tribes which might be termed the aristocratic, the chiefs and their relatives, the aged men and distinguished warriors, stood aloof from a conspiracy which seemed desperate and hopeless, while the younger warriors ‘listened with credulity to the Prophet, and were kindled into ardor by the eloquence of Tecumthé. The latter continued to travel from tribe to tribe, pursuing the darling object of his life, with incessant labor, commanding respect by the dignity and manliness of his character, and winning adherents by the boldness of his public addresses, as well as by the subtlety with which, in secret, he appealed to individual interest or passion.

This state of things continued for several years. Most of the Indian tribes were ostensibly at peace with the United States; but the tribes, though unanimous in their hatred against the white people, were divided in opinion as to the proper policy to be pursued, and distracted by intestine conflicts. The more prudent deprecated an open rupture with our government, which would deprive them of their annuities, their traffic, and the presents which flowed in upon them periodically, while the great mass thirsted for revenge and plunder. The British authorities in Canada, alarmed at the rapid spread of our settlements, dispersed their agents along the frontier, and industriously fomented- these jealousies. Small parties of Indians scoured the country, committing thefts and murders unacknowledged by their tribes, but undoubtedly approved, if not expressly sanctioned, at their council fires.

The Indiana territory having been recently organized, and Governor Harrison being invested with the office of superintendent of Indian affairs, it became his duty to hold frequent treaties with the Indians; and, on these occasions, Tecumthé and the Prophet were prominent men. The latter is described as the most graceful and agreeable of Indian orators; he was easy, subtle, arid insinuating not powerful, but persuasive in argument; and, it was remarked, that he never spoke when Tecumthé was present. He was the instrument, and Tecumthé the master-spirit, the bold warrior, the able, eloquent, fearless speaker, who, in any assembly of his own race, awed all around him by the energy of his character, and stood forward as the leading individual.

The ground assumed by these brothers was, that all previous treaties between the Indians and the American government were invalid, having been made without authority. They asserted that the lands inhabited by the Indians, belonged to all the tribes indiscriminately that the Great Spirit had given them to the Indians for hunting-grounds that each tribe had a right to certain tracts of country so long as they occupied them, but no longer that if one tribe moved away, another might take possession; and they contended for a kind of entail, which prevented any tribe from alienating that to which he had only a present possessory right. They insisted, therefore, that no tribe had authority to transfer any soil to the whites, without the assent of all; and that, consequently, all the treaties that had been made were void. It was in support of these plausible propositions that Tecumthé made his best speeches, and showed especially his knowledge of human nature, by his artful appeals to the prejudices of the Indians. He was, when he pleased to be so, a great demagogue; and when he condescended to court the people, was eminently successful. In his public harangues he acted on this principle; and, while he was ostensibly addressing the governor of Indiana, or the chiefs who sat in council, his speeches, highly inflammatory, yet well digested, were all, in fact, directed to the multitude. It was on such an occasion that, in ridiculing the idea of selling a country, he broke out in the exclamation “Sell a country! why not sell the air, the clouds, and the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children?”

We select the following passages from the “Memoirs of General Harrison.”

“In 1809, Governor Harrison purchased from the Delaware, Miami, and Potawatimie, a large tract of country on both sides of the Wabash, and extending up that river about sixty miles above Vincennes. Tecumthé was absent, and his brother, not feeling himself interested, made no opposition to the treaty; but the former, on his return, expressed great dissatisfaction, and threatened some of the chiefs with death, who had made the treaty. Governor Harrison, hearing of his displeasure, dispatched a messenger to invite him to come to Vincennes, and to assure him, ‘that any claims he might have to the lands which had been ceded, were not affected by the treaty; that he might come to Vincennes and exhibit his pretensions, and if they were found to be valid, the land would be either given up, or an ample compensation made for it.’

“Having no confidence in the faith of Tecumthé, the governor directed that he should not bring with him more than thirty warriors; but he came with four hundred, completely armed. The people of Vincennes were in great alarm, nor was the governor without apprehension that treachery was intended. This suspicion was not diminished by the conduct of the chief, who, on the morning after his arrival, refused to hold the council at the place appointed, under an affected belief that treachery w r as intended on our side.

“A large portico in front of the governor’s house had been prepared for the purpose with seats, as well for the Indians as for the citizens who were expected to attend. When Tecumthé came from his camp, with about forty of his warriors, he stood off, and on being invited by the governor, through an interpreter, to take his seat, refused, observing that he wished the council to be held under the shade of some trees in front of the house. When it was objected that it would be troublesome to remove the seats, he replied, that it would only be necessary to remove those intended for the whites that the red men were accustomed to sit upon the earth, which was their mother, and that they were always happy to recline upon her bosom.’

“At this council, held on the 12th of August, 1810, Tecumthé delivered a speech, of which we find the following report, containing the sentiments uttered, but in a language very different from that of the Indian orator:

“I have made myself what I am; and I would that I could make the red people as great as the conceptions of my mind, when I think of the Great Spirit that rules over all. I would not then come to Governor Harrison to ask him to tear the treaty; but I would say to him, Brother, you have liberty to return to your own country. Once there was no white man in all this country: then it belonged to red men, children of the same parents, placed on it by the Great Spirit to keep it, to travel over it, to eat its fruits, and fill it with the same race once a happy race, but now made miserable by the white people, who are never contented, but always encroaching. They have driven us from the great salt water, forced us over the mountains, and would shortly push us into th lakes but we are determined to go no farther. The only way to stop this evil, is for all the red men to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land, as it was at first, and should be now for it never was divided, but belongs to all. No tribe has a right to sell, even to each other, much less to strangers, who demand all, and will take no less. The white people have no right to take the land from the Indians who had it first it is theirs. They may sell, but all must join. Any sale not made by all, is not good. The late sale is bad it was made by a part only. Part do not know how to sell. It requires all to make a bargain for all.’

“Governor Harrison, in his reply, said, that the white people, when they arrived upon this continent, had found the Miamis in the occupation of all the country of the Wabash; and at that time the Shawanese were residents of Georgia, from which they were driven by the Creeks. That the lands had been purchased from the Miamis, who were the true and original owners of it. That it was ridiculous to assert that all the Indians were one nation; for if such had .been the intention of the Great Spirit, he would not have put six different tongues into their heads, but would have taught them all to speak one language. That the Miamis had found it for their interest to sell a part of their lands, and receive for them a further annuity, in addition to what they had long enjoyed, and the benefit of which they had experienced, from the punctuality with which the seventeen fires complied with their engagements; and that the Shawanese had no right to come from a distant country, to control the Miamis in the disposal of their own property.’

“The interpreter had scarcely finished the explanation of these remarks, when Tecumthe fiercely exclaimed, ‘It is false!’ and giving a signal to his warriors, they sprang upon their feet, from the green grass on which they were sitting, and seized their war-clubs. The governor, and the small train that surrounded him, were now in imminent danger. He was attended by a few citizens, who were unarmed. A military guard of twelve men, who had been stationed near him, and whose presence was considered rather as an honorary than a defensive measure being exposed, as it was thought unnecessarily, to the heat of the sun in* a sultry August day, had been humanely directed by the governor to remove to a shaded spot at some distance. But the governor, retaining his presence of mind, rose and placed his hand upon his sword, at the same time directing those of his friends and suite who were about him, to stand upon their guard. Tecumthe addressed the Indians in a passionate tone, and with violent gesticulations. Major- G. R. C. Floyd, of the U. S. army, who stood near the governor, drew his dirk; Winnemak, a friendly chief, cocked his pistol, and Mr. Winans, a Methodist preacher, ran to the governor’s house, seized a gun, and placed himself in the door to defend the family. For a few minutes all expected a bloody re-encounter. The guard was ordered up, and would instantly have fired upon the Indians, had it not been for the coolness of Governor Harrison, who restrained them. He then calmly, but authoritatively, told Tecumthe that ‘he was a bad man that he would have no further talk with him that he must now return to his camp, and take his departure from the settlements immediately.’

“The next morning, Tecumthé having reflected on the impropriety of his conduct, and finding that he had to deal with a man as bold and vigilant as himself, who was not to be daunted by his audacious turbulence, nor circumvented by his specious maneuvers, apologized for the affront he had offered, and begged that the council might be renewed. To this the governor consented, sup pressing any feeling of resentment which he might naturally have felt, and determined to leave no exertion untried, to carry into effect the pacific views of the government. It was agreed that each party should have the same attendance as on the previous day; but the governor took the precaution to place himself in an attitude to command respect, and to protect the inhabitants of Vincennes from violence, by ordering two companies of militia to be placed on duty within the village.

“Tecumthé presented himself with the same undaunted bearing which always marked him as a superior man; but he was now dignified and collected, and showed no disposition to resume his former insolent deportment. He disclaimed having entertained any intention of attacking the governor, but said he had been advised by white men to do as he had done. Two white men British emissaries undoubtedly had visited him at his place of residence, and told him that half the white people were opposed to the governor, and willing to relinquish the land, and urged him to advise the tribes not to receive pay for it, alleging that the governor would soon be recalled, and a good man put in his place, who would give up the land to the Indians. The governor inquired whether he would forcibly oppose the survey of the purchase. He replied, that he was determined to adhere to the old boundary. Then arose a Wyandot, a Kickapoo, a Potawatimie, an Ottawa, and a Winnebago chief, each declaring his determination to stand by Tecumthé. The governor then said, that the words of Tecumthé should be reported to the President, who would take measures to enforce the treaty; and the council ended.

“The governor, still anxious to conciliate the haughty savage, paid him a visit next day at his own camp. He was received with kindness and attention his uniform courtesy and inflexible firmness having won the respect of the rude warriors of the forest. They conversed for some time, but Tecumthe obstinately adhered to all his former positions; and when Governor Harrison told him that he was sure the President would not yield to his pretensions, the chief replied, ‘ Well, as the great chief is to determine the matter, I hope the Great Spirit will put sense enough into his head to induce him to direct you to give up this land. It is true, he is so far off, he will not be injured by the war. He may sit still in his town, and drink his wine, while you and I will have to fight it out.'”

The two brothers, who thus acted in concert, though, perhaps, well fitted to act together, in the prosecution of a great plan, were widely different in character. Tecumthé was bold and sagacious a successful warrior, a fluent orator, a shrewd, cool-headed, able man, in every situation in which he was placed. His mind was expansive and generous. He detested the white man, but it was with a kind of benevolent hatred, based on an ardent love for his own race, and which rather aimed at the elevation of the one than the destruction of the other. He .had sworn eternal vengeance against the enemies of his race, and he held himself bound to observe towards them no courtesy, to consent to no measure of conciliation, until the purposes to which he had devoted himself should be accomplished. He was fall of enthusiasm, and fertile of expedient. Though his whole career was one struggle against adverse circumstances, he was never discouraged, but sustained himself with a presence of mind, and an equability of temper which showed the real greatness of his character.

The following remarkable circumstance may serve to illustrate the penetration, decision, and boldness of this warrior-chief: He had been down south, to Florida, and succeeded in instigating the Serninole in particular, and portions of other tribes, to unite in the war on the side of the British. He gave out, that a vessel, on a certain day, commanded by red coats, would be off Florida, filled with guns and ammunition, and supplies for the use of the Indians. That no mistake might happen in regard to the day on which the Indians were to strike, he prepared bundles of sticks each bundle containing the number of sticks corresponding to this number of days that were to intervene between the day on which they were received, and the day of the general onset. The Indian practice is, to throw away a stick every morning they therefore, no mistake in the time. These sticks Tecumthé caused to be painted red. It was from this circumstance that, in the former Seminole war, these Indians were called “Red Sticks.” In all this business of mustering tribes, Tecumthé used great-caution. He supposed inquiry would be made as to the object of his visit. That his plans might not be suspected, he directed the Indians to reply to any questions that might be asked about him, by saying, that he had counseled them to cultivate the ground, abstain from ardent spirits, and live in peace with the white people. On his return from Florida, he went among the Creeks, in Alabama, urging them to unite with the Seminoles. Arriving at Tuckhabatchee, a Creek town on the Tallapoosa river, he made his way to the lodge of the chief called the Big Warrior. He explained his object; delivered his war-talk presented a bundle of sticks gave a piece of wampum and a war-hatchet; all which the Big Warrior took. But Tecumthé, reading the spirit and intentions of the Big Warrior, looked him in the eye, and pointing his finger towards Ids face, said, “Your blood is white You have taken my talk, and the sticks, and the wampum, and the hatchet, but you do not mean to fight. I know the reason. You do not believe the Great Spirit has sent me. You shall know. I leave Tuckhabatchee directly and shall go straight to Detroit. When I arrive there, I will stamp on the ground with my foot, and shake down every house in Tuckhabatchee.” So saying, he turned, and left the Big Warrior in utter amazement, both at his manner and his threat, and pursued his journey. The Indians were struck no less with his conduct than was the Big Warrior, and began to dread the arrival of the day when the threatened calamity would befall them. They met often, and talked over this matter and counted the days carefully, to know the day when Tecumthé would reach Detroit. The morning they had fixed upon as the day of his arrival at last came. A mighty rumbling was heard the Indians all ran out of their houses the earth began to shake; when, at last, sure enough, every house in Tuckhabatchee was shaken down! The exclamation was in every mouth, ” Tecumthé has got to Detroit !” The effect was electric. The message he had delivered to the Big Warrior was believed, and many of the Indians took their rifles and prepared for the war.

The reader will not be surprised to learn that an earthquake had produced all this; but he will be, doubtless, that it should happen on the very day on which Tecumthé arrived at Detroit, and in exact fulfillment of his threat. It was the famous earthquake of New Madrid, on the Mississippi. We received the foregoing from the lips of the Indians, when we were at Tuckhabatchee, in 1827, and near the residence of the Big Warrior. The anecdote may, therefore, be relied on. Tecumthé’s object, doubtless, was, on seeing that he had failed, by the usual appeal to the passions, and hopes, and war spirit of the Indians, to alarm their fears, little dreaming, himself, that on the day named, his threat would be executed with such punctuality and terrible fidelity.

Tecumthé was temperate in his diet, used no ardent spirits, and did not indulge in any kind of excess. Although several times married, he had but one wife at a time, and treated her with uniform kindness and fidelity; and he never evinced any desire to accumulate property, or to gratify any sordid passion. Colonel John Johnston, of Piqua, who knew him well, says, ” He was sober and abstemious; never indulging in the use of liquors, nor catering to excess; fluent in conversation, and a great public speaker. He despised dress, and all effeminacy of manners; he was disinterested, hospitable, generous, and humane the resolute and indefatigable advocate of the rights and independence of the Indians.” Stephen Ruddle, a Kentuckian, who was captured by the Indians in childhood, and lived in the family of Tecumthé, says of him, His talents, rectitude of deportment, and friendly disposition, commanded the respect and regard of all about him;” and Governor Cass, in speaking of his oratory, says, “It was the utterance of a great mind, roused by the strongest motives of which human nature is susceptible, and developing a power and a labor of reason which commanded the admiration of the civilized, as justly as the confidence and pride of the savage.”

The Prophet possessed neither the talents nor the frankness of his brother. As a speaker, he was fluent, smooth, and plausible, and was pronounced by Governor Harrison the most graceful and accomplished orator he had seen among the Indians; but he was sensual, cruel, weak, and timid. Availing himself of the superstitious awe inspired by supposed intercourse with the Great Spirit, he lived in idleness, supported by the presents brought him by his deluded followers. The Indians allow polygamy, but deem it highly discreditable in any one to marry more wives than he can support; and a prudent warrior always regulates the number of his family by his capacity to provide food. Neglecting this rule of propriety, the Prophet had an unusual number of wives, while he made no effort to procure a support for his household, and meanly exacted a subsistence from those who dreaded his displeasure. An impostor in every thing, he seems to have exhibited neither honesty nor dignity of character in any relation of life.

We have not room to detail all the political and military events in which these brothers were engaged, and which have been related in the histories of the times. An account of the battle of Tippecanoe, which took place in 1811, and of the intrigues which led to an engagement so honorable to our arms, would alone fill more space than is allotted to this article. On the part of the Indians it was a fierce and desperate assault, and the defense of the American general was one of the most brilliant and successful in the annals of Indian warfare; but Tecumthé was not engaged iii it, and the Prophet, who issued orders from a safe position, beyond the reach of any chance of personal exposure, performed no part honor able to himself, or important to the result. He added cowardice to the degrading traits which had already distinguished his character, and from that time his influence decreased. At the close of the war, in 1814, he had ceased to have any reputation among the Indians.

The latter part of the career of Tecumthé was as brilliant as it was unfortunate. He sustained his high reputation for talent, courage, and good faith, without achieving any advantage for the unhappy race to whose advancement he had devoted his whole life. In the war between the United States and Great Britain, which commenced in 1812, he was an active ally of the latter, and accompanied their armies at the head of large bodies of Indians. He fought gallantly in several engagements, and fell gloriously in the battle of the Thames, where he is supposed, with reason, to have fallen in a personal conflict with Colonel Richard M. Johnson, of Kentucky.

One other trait in the character of this great man deserves to be especially noticed. Though nurtured in the forest, and accustomed through life to scenes of bloodshed, he was humane. While a mere boy, he courageously rescued a woman from the cruelty of her husband, who was beating her, and declared that no man was worthy of the name of a warrior who could raise his hand in anger against a woman. He treated his prisoners with uniform kindness; and, on several occasions, rescued our countrymen from the hands of his enraged followers.

The Prophet was living, when we last heard of him, west of the Mississippi, in obscurity.