Arader Galleries

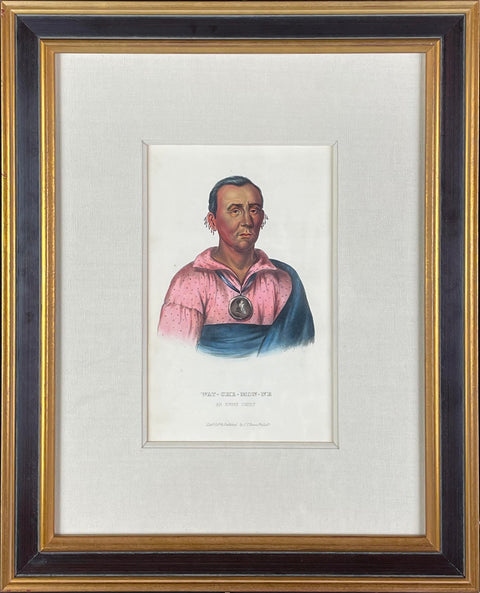

WAT-CHE-MON-NE, An Ioway Chief

Pickup currently unavailable

Thomas McKenney (1785-1859) & James Hall (1793-1868)

WAT-CHE-MON-NE, An Ioway Chief

From History of the Indian Tribes of North America with Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of the Principal Chiefs

Published: Philadelphia, VOL I: 1837, VOL ll: 1842, VOL lll: 1844

Hand-colored lithograph

Sheet size: approx. 14.5 x 20”

The Orator, the third chief of the Ioways was born at the old Ioway ,village, on Des Moines River, at this time occupied by Keokuk, and, in 1838, was about fifty-two years of age. In recalling his earliest recollections, he tells, as the Indians mostly do, that he began in boyhood to kill small game with the bow and arrow. When he became large enough to use firearms, he procured a fowling-piece, or, as the phrase is upon the border, a shot-gun-a weapon considered of far inferior dignity to the more deadly rifle. But such was the awe inspired in his mind by the effects of gunpowder, that he was at first afraid to discharge his gun, and threw a blanket over his breast and shoulder before he ventured to level the piece. His first experiment was upon a wild turkey, which he killed, and after that he hunted without fear. This occurred before he was thirteen, for at that age he killed deer with his gun. At sixteen, he went to war, killed an Osage, and took a piece of a scalp. His leader, in that occasion, was Wenugana, or, The man who gives his opinion. After a long tune, he again went out with a war-party under Notoyaukee, or One rib. Approaching a camp of the Missouris, some of their swiftest young men went forward, dashed into the camp, despatched three men, and returned, saying they had killed all. He was in the same affair with Notchemine, when the eleven were killed, and remembers that among the slain was a great chief. He slew none himself; but struck the dead and took three scalps, which is regarded as the greater exploit.

Soon after Thomas L. McKenney was appointed Superintendent of Indian Trade in 1816, he struck upon the idea of creating an archive to preserve the artifacts, implements, and history of the Native Americans. The Archives of the American Indian became the first national collection in Washington and were curated with great care by McKenney through his tenure as Superintendent and also when he served as the first head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs beginning in 1824. Artist Charles Bird King arrived in town in 1822 and, during a visit to his studio, McKenney was inspired to add portraits to the archives. King would, for the following twenty years, capture many of the visiting Indian dignitaries, as well as make copies of watercolors created in the field by the less able James Otto Lewis. Many saw the great value in preserving what was already known to be a vanishing race, but others in government criticized the expenses incurred. The visiting Indian delegations who had come to Washington to meet with the "Great Father" (their name for the president) would inevitably tour the Indian gallery, which was housed in the War Department building, and were generally impressed, many requesting that their portrait be painted and added to the collection. This seemed to help smooth relations during the often tense treaty negotiations.

McKenney was preparing to publish a collection of the Indian portraits when he lost his position at the Bureau during Andrew Jackson's house cleaning in 1830. This seemed like an omen, as many other setbacks befell the project: publishers went bankrupt, investors dropped out, historical information became unobtainable, and expenses soared. McKenney finally enlisted Ohio jurist and writer James Hall to assist with the project, making him a partner. Hall was able to complete the individual biographies of each subject and put the finishing touches on the general history. Six years passed between the original prospectus and the issue of the first part. In that time, James Otto Lewis, who was likely bitter that he would receive no credit for the King-reworked portraits that he sent to the Archives, beat McKenney to the market with his own Aboriginal Port-Folio in 1835. Unfortunately for Lewis, the illustrations were of inferior quality and very few of its later numbers were ever completed. McKenney and Hall's History of the Indian Tribes of North America, on the other hand, was a resounding artistic success. The lithographs were of such high quality, comparable to the best work from Europe, that John James Audubon commissioned the lithographer James T. Bowen to provide illustrations for a revised edition of his Birds of America. Indian Tribes wasn't a financial success, however, for its high price prohibited all but the wealthy and public libraries from subscribing to it. This and the depression after the panic of 1837 both contributed to the work going through several publishers and lithographers before its completion. King's original paintings were eventually transferred to the Smithsonian Institute, where most of them perished in the January 1865 fire. A number of the paintings exist in the form of contemporary copies made by King and his students, but the present work is by far the most complete record of this important collection.